Participatory planning on the neighbourhood level has been experimented with, and in some cities established practice, for many years. Next Hamburg has taken participatory planning to the next scale, experimenting with crowd-sourcing a vision for 2030 on the city level. Since January 2013, they have been replicating the experiment in Bangalore.

Next Hamburg’s goal is two-fold: (1) to build up a comprehensive and citizen-driven future vision that will give impulse to local urban development and (2) to help projects with large community support get realised. The project consists of a mix between offline workshops and meetings and online planning and dialogue through the Next Hamburg website.

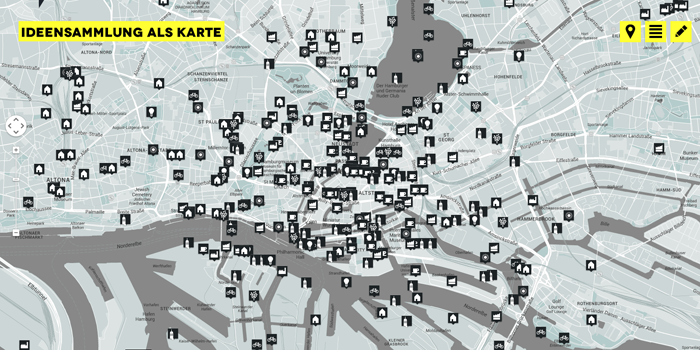

Next Hamburg has been running since 2009 and 765 ideas have been proposed online. That seems a considerable number, but Hamburg has almost 2 million inhabitants, which makes the total seem rather paltry. In terms of dialogue, the results also seem meagre. The most “liked” project only has 75 likes and reactions tend to be brief responses to the main idea, rather than forming a real dialogue. Offline, the Future Camp in February 2012 seems to have been considerably more of a success, with almost 2000 participants and guests.

Next Hamburg Ideas Map. source: //www.nexthamburg.de

Based on the ideas resulting from the website and offline workshops, a citizen’s vision was published in late 2012. Online, the vision consists of 35 scenarios on various themes. Together, they form a colourful and creative mix of ideas, yet they seem to be lacking in coherence. Important themes such as economic growth and recreation are only thinly touched on.

CHALLENGES

Next Hamburg shows that there are still considerable challenges in engaging people to participate in these kinds of activities. These challenges are probably even bigger in a context like Bangalore. Next Bangalore has had 182 posts since its launch in January 2013, still far below the goal of 1000 to produce a first city vision. Crowd-sourcing a city vision might be a slow process indeed.

Moreover, in a context where internet access is still very unequal between different social classes, it is debatable whether it is possible to create a vision that represents the views of a broad cross-section of the population. Even though there is also a physical location where people can submit their ideas, poor people may lack the time and financial resources to make the trip.

As a result, Next Bangalore risks becoming an example of how public participation, despite its apparently open character, could become gentrified. There is a risk that the process could result in a vision from the upper classes, which might have detrimental effects for others. Slum residents, for example, might be threatened by the reductive upper-class view of slums as aesthetic nuisances, as described by Asher Ghertner in one of his articles. And indeed, some of the posts on Next Bangalore actually request the removal of slums.

Nevertheless, Next Hamburg and Next Bangalore are valuable experiments. The ideas collected can be valuable input for professional planners and designers and point at themes that need to be worked on in the future. Maybe most importantly, the collection of ideas shows that non-experts can think (just as) creatively as professionals about the future of the city. As such, Next Hamburg is a great example for those who want to promote increased public participation in city development.